The Rundown on Different Stroke Scales

Note: This article is written off of a guest writer’s own work. The guest writer is a current EMT-Basic pursuing Paramedic education. Based off the site owner’s own interactions with this provider, he is a competent, driven, and overall quality provider with a plethora of field experience. The content of this article was initially assessing and comparing the various prehospital stroke scales for weaknesses.

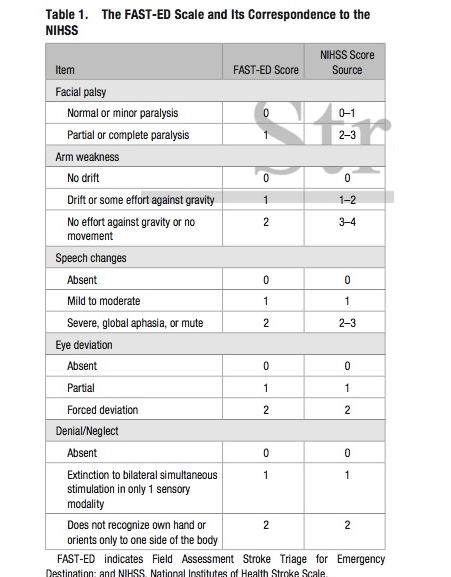

The FAST-ED

In recent years, both prehospital and hospital clinical institutions have been moving towards a generalized FAST-ED stroke assessment tool. The Field Assessment Stroke Triage for Emergency Destination (FAST-ED) scale is designed to simplify assessment of stroke while providing additional quantitative grading to decide the likelihood of a large vessel occlusion (LVO) ongoing versus a smaller ischemic stroke. It relies on five components: facial palsy, arm drift, speech abnormalities, eye deviation, and denial/neglect of sensations. Each item is scored on a scale of 0 to 2 (except for facial palsy, which uses a 0 or 1), with a 0 meaning absence of symptoms and a 2 meaning severe symptoms suggesting stroke for that assessment item.

This tool is unique in that it combines both the assessment techniques of the Cincinnati prehospital stroke scale and the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS) scale. The Cincinnati provides a rough screening tool to determine the likelihood of a presence occurring in general, while the LAMS tool is used to narrow down and quantitatively state a likelihood for the stroke being a large vessel occlusion. FAST-ED combines these tools to both identify the possibility of a stroke ongoing and scoring it so that providers have more information about end destination. With this tool, field providers can both identify that a patient is likely experiencing a stroke and direct the patient towards an appropriate transport destination according to the score. Patients experiencing large vessel occlusions will benefit from a potentially longer transport to a thrombectomy-capable, full stroke center in many cases versus transporting to a primary stroke center that may be slightly closer.

As with any tool, FAST-ED must be used in conjunction with the provider’s own clinical assessment, knowledge, and the realities of their individual EMS system. Choosing a thrombectomy-capable stroke center versus a primary stroke center often makes little sense for EMS providers in urban centers where all are equally close and capable. However, tools such as FAST-ED can have a major difference for rural and lower density suburban systems, where a primary and thrombectomy-capable/comprehensive stroke center may be 20 or 25 minutes apart.

The Research Behind Fast-ED

The FAST-ED scale was developed off of a sample size of 727 patients seen within two university hospitals (Lima et al., 2016). Patients were provided the FAST-ED scale and confirmed using head CT scans. Patients that had an ongoing cerebral hemorrhage or were ineligible to receive the necessary contrast dye were not included in the study (Lima et al., 2016). Throughout the course of the study, researchers found that the FAST-ED tool was effective both at recognizing the presence of a stroke, but also accurately grading the approximate size of the occlusion present. At scores of 3 or above, the FAST-ED was found to be most sensitive and correctly indicated presence of an LVO (Lima et al., 2016).

FAST-ED was developed in order to provide a quicker tool for evaluation of prehospital strokes. It has quickly become a prominent stroke assessment tool for both emergency department and EMS use.

Cincinnati Stroke Scale

The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke scale was developed as a means of to rapidly identify broad categories of strokes. It uses a scale of 0-4, with a positive finding in each assessment area assigning a 1 in that category. With scores of 3, the Cincinnati scale is able to accurately assess for presence of an LVO similar to other stroke scales (Richards et al., 2018).

The benefit of the Cincinnati scale is that it is used to rapidly identify strokes in the field with very little intensive assessment. 1 positive finding, when combined with clinical context, under this scale indicates at least a 72 percent probability that the patient is experiencing an active stroke (Sinz et al., 2011). The likelihood increases significantly if more than 1 symptom is present.

EMS systems often utilize this scale as their first line stroke assessment tool. In algorithm guidelines, it can be used to stem further stroke assessment such as LAMS scoring and class the patient as a stroke patient for the call. The Cincinnati is not ideal when used as the only stroke assessment tool for the patient, and should be paired with other tools to provide as comprehensive of an assessment as possible.

Los Angeles Motor Score

The Los Angeles Motor Score (LAMS) is a robust prehospital stroke gauging tool. It is not primarily used to identify an active stroke, but rather grade the severity of the neurological symptoms and likelihood that the patient is experiencing an LVO.

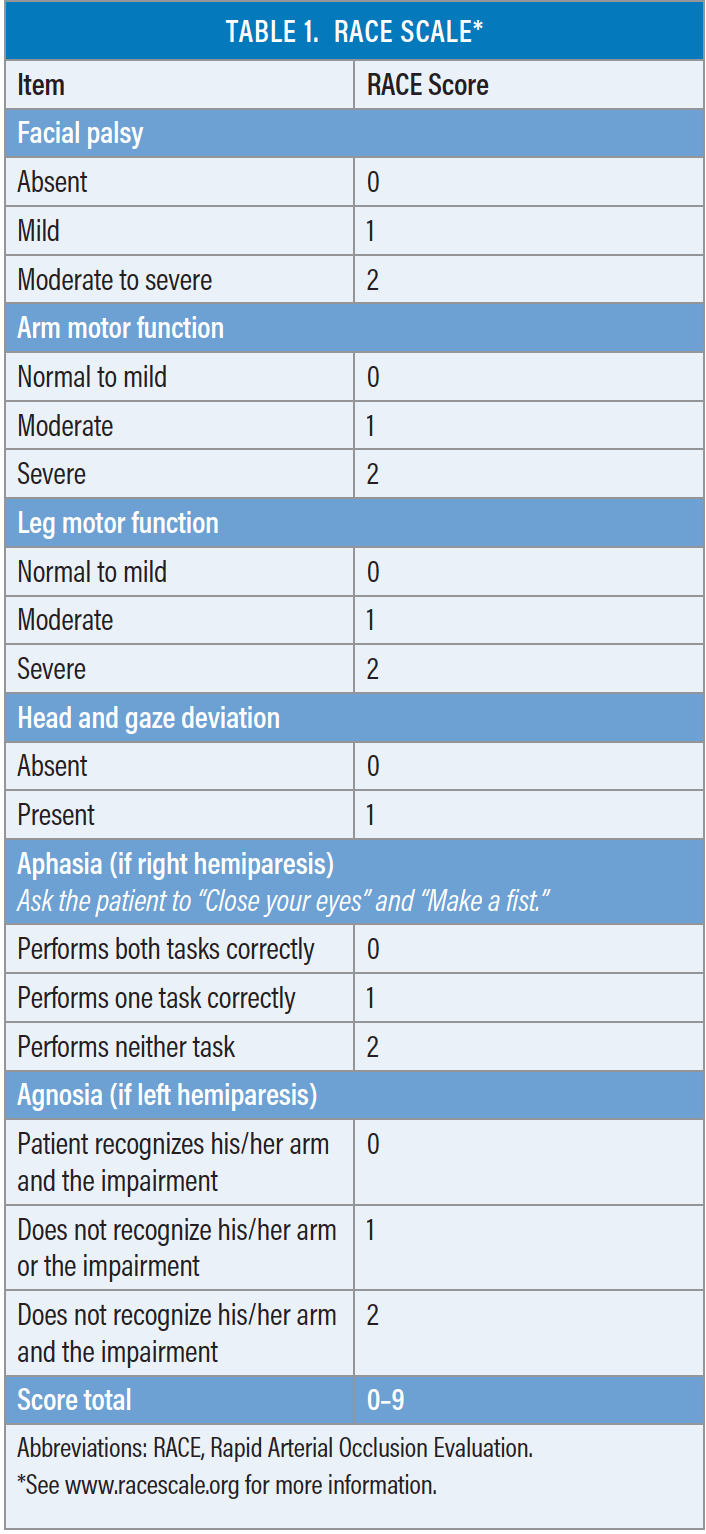

Rapid Arterial oCclusion Evaluation (RACE)

The Rapid Arterial oCclusion Evaluation (RACE) Scale for Stroke is a multi-step stroke assessment tool that primarily focuses on gauging the size and possible location of a large vessel occlusion. It does this by using a tree-like approach, with a different assessment technique used depending on the patient’s presentation and side of body affected. If the patient has left sided hemiparesis, then the patient will be scored for agnosia and sensory deficits. If the patient has right sided hemiparesis, then the patient will be scored for aphasia and speech deficits further. The scale runs from 0-9. The primary use of this tool is to identify a large vessel occlusion and help EMS providers steer hospital transport decisions in the case of stroke.

When using the RACE scale, a score over 5 is likely to indicate the presence of an LVO stroke and thus patients with said score are best served by transport to a comprehensive/mechanical-capable stroke center (Smith et al., 2018).

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is an extremely comprehensive stroke scale tool that allows providers to both identify the likelihood of stroke presence and gauge its severity based off presenting neurological symptoms. It uses 15 assessment areas to generate a score of 0-42, with higher scores indicating higher severity and higher likelihood for a large vessel occlusion (Physiopedia, n.d.).

The NIHSS is the most extensive and commonly used stroke scale currently seeing clinical use. It is not commonly used prehospital, however. Neurologists largely use the NIHSS in hospital during initial assessment, and then provide repeats at different stages of the patient’s recovery in order to assess remaining neurological deficits. The NIHSS is a particularly versatile tool because it can accurately predict outcomes based off the initial baseline score taken during the acute stroke episode (Adams et al., 1999).

Conclusion & Personal Note

Stroke assessments are an ongoing, developing science., and no single tool is able to accurately and consistently identify all strokes. The golden tool for stroke assessment remains imaging and head CT, at the end of the day. These tools and other assessment findings are merely a means to identify patients that should be referred to rapid imaging.

The original inspiration for this article tells a personal story about the shortcomings of stroke assessment tools. The provider was dispatched to a patient experiencing a medical emergency. Upon arrival, the patient was agitated, had hypertension with systolic averaging 200s and above, and was lacrimating blood. The patient had a positive Cincinnati score and a LAMS score of 0. The patient did not present with slurred speech, abnormal weakness, imbalance, or any other motor issue. However, the patient did have neglect/anesthesia of 3 digits on one hand. Based on those findings, the patient was deemed a stroke alert and was transported to a stroke center. From there, the patient underwent rapid imaging and was found to have a mild ischemic stroke.

The patient had a normal level of consciousness and remained responsive the whole time. The patient was discharged with a good neurological recovery. While the patient would not have scored anything on the LAMS score, for instance, the Cincinnati findings were enough to accurately identify a developing stroke and get proper treatment for the patient within the time window.

It is important to remember that nothing can rule out a stroke. However, these tools and our understanding of clinical pictures can help us to rule in a likely stroke. The patient with generalized weakness and inability to follow commands may score positively on a stroke scale, but the clinical context of the patient having a UTI ongoing for the past 4 days, being febrile without relief for 3 years, and being hypotensive with persistent tachycardia may point us to further investigate sepsis.

Whenever a patient with unexplainable neuro symptoms is discovered, it is important to conduct a full assessment and run through both reversible and reportable causes. Reversible causes are things that we can correct prehospitally - things like blood glucose, hypovolemia, etc. - while reportable causes are things that will require assessment and treatment in hospital. Both are important to recognize as the hospital may not investigate something or may look at the patient’s clinical picture differently than us.

Works Cited

Adams, H. P., Davis, P. H., Leira, E. C., Chang, K. C., Bendixen, B. H., Clarke, W. R., Woolson, R. F., & Hansen, M. D. (1999). Baseline NIH Stroke Scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: A report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology, 53(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.53.1.126

Lima, F. O., Silva, G. S., Furie, K. L., Frankel, M. R., Lev, M. H., Camargo, R. C., Haussen, D. C., Singhal, A. B., Koroshetz, W. J., Smith, W. S., & Nogueira, R. G. (2016). Field Assessment Stroke Triage for Emergency Destination. Stroke, 47(8), 1997–2002. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.116.013301

Physiopedia. (n.d.). NIH Stroke Scale. https://www.physio-pedia.com/NIH_Stroke_Scale

Richards, C. T., Huebinger, R., Tataris, K. L., Weber, J. M., Eggers, L., Markul, E., Stein-Spencer, L., Pearlman, K. S., Holl, J. L., & Prabhakaran, S. (2018). Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale Can Identify Large Vessel Occlusion Stroke. Prehospital Emergency Care, 22(3), 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1387629

Sinz, E., Navarro, K., & Soderberg, E. S. (2011). Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support: Provider Manual (Professional ed.). American Heart Association.

Smith, E. E., Kent, D. M., Bulsara, K. R., Leung, L. Y., Lichtman, J. H., Reeves, M. J., Towfighi, A., Whiteley, W. N., & Zahuranec, D. B. (2018). Accuracy of Prediction Instruments for Diagnosing Large Vessel Occlusion in Individuals With Suspected Stroke: A Systematic Review for the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke, 49(3). https://doi.org/10.1161/str.0000000000000160